An ecumenical panel explores the extent of that sin and how the church can heal

July 30, 2022

Photo by Jon Tyson via Unsplash

People recruiting for a white supremacist cause on a Sunday morning will find more success at their local church than at their local coffee shop.

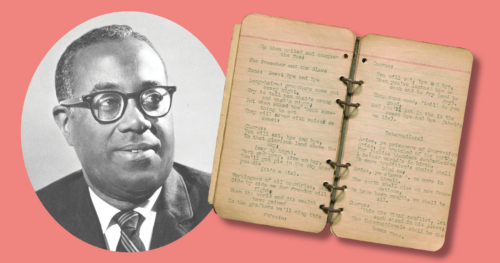

That’s what research revealed for Dr. Robert P. Jones’ most recent book, “White Too Long: The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity,” and it’s a fact he shared during the recent White Supremacy and American Christianity webinar attended by about 2,500 people. Jones, the CEO and founder of the Public Religion Research Institute, joined Fr. Bryan Massingale, the author of “Racial Justice and the Catholic Church” and the Nancy Buckman Chair in Applied Ethics as well as the Senior Ethics Fellow at Fordham University’s Center for Ethics Education. Dr. Marcia Chatelain, winner of the 2021 Pulitzer Prize in History for her book “Franchise: The Golden Arches in Black America” and a professor of history and African American Studies at Georgetown University, answered Jones’ and Massingale’s presentations with her own critique.

The NETWORK Lobby for Catholic Social Justice sponsored the online conference, with help from organizations including the Center for Faith, Justice & Reconciliation at Union Presbyterian Seminary.

Massingale said when he read that statement in Jones’ book, “it jumped out at me. There is something about Christianity that inclines white people to be more racist. I want those participating to pause and let that sink in.”

“We have this idea of people who marched with torches in Charlottesville or those who stormed the Capitol in January of last year,” Massingale said. “But what we are talking about is people in church, that white Christianity itself incubates a sense of white superiority … I remember the first time I saw an image of a Black Christ. A part of me said, ‘what?’ I had been malformed and deformed. God and Jesus being white is the image I got.”

“If you believe a white person rules in the heavens, you believe they should rule here on Earth,” Massingale said. “The idea of representation isn’t idle. These things have real political impact and create a culture of white Christian nationalism.”

For many people, just the term “white supremacy” is hard to hear, Jones said. “We think of old photos of people burning a cross. It’s a convenient way to think about white supremacy because we don’t know anybody like that.”

But in “any city we go to” there’s a history of redlining, a “straight-up expression of white supremacy,” Jones said. In many communities, churches were seen as institutions protecting the neighborhood from non-white people entering them. Jones’ own grandfather was a deacon in his church. It was his job to stand outside the church before worship “to make sure no non-white person entered the sanctuary. That history is very near to us and is certainly very present with us in many ways.”

Massingale remembers as a seventh grader the first time attending Mass in a new community. Members of the congregation “told us you would be more comfortable attending your former church.” Their message, he said, is “this church belongs to white people.”

When Massingale presents on racism and white supremacy, “People ask, ‘How can I talk about this in my parish and not make white people uncomfortable?’ I turn it around: ‘Why is it the only group that is never supposed to feel uncomfortable talking about race is white people?’”

In January, Jones published a piece called “The Sacred Work of White Discomfort.” He wonders: What kind of growth do we get without discomfort?

“Do we want to be comfortable, or do we want to be free?” Jones said during the webinar. Do we want to keep the status quo, “or work out our salvation with fear and trembling? This commitment to white supremacy is the air we breathe and the water we swim in,” Jones said. “We don’t see how it has distorted the gospel and affected our ability to love one another.”

“If we want to hand down the faith to our kids, we need to think about the work that has to be done,” Jones said. “I can try to find a comfortable faithfulness of my ancestors or I can be faithful to my kids — but I cannot do both.”

Mike Ferguson, Editor, Presbyterian News Service

Let us join in prayer for:

PC(USA) Agencies’ Staff

Jacqueline Boersema, Director Financial Education, Board of Pensions

Raymond Bonwell, Corporate Secretary, Board of Pensions

Let us pray

Dear God, thank you for hearing our cries to end the injustice of racism and to become the beloved community. Help us to hear and respond to your call on our lives to do justice, love mercy and walk humbly with you. Amen.